Solving for Scotch Tape

I remember sitting in a business management course at the University of Denver when our wise, colorful professor presented us with a scenario: Imagine we were the general manager of an office. In the month of December, an inventory analysis of office supplies showed a 600% increase in the usage of scotch tape. “What should you do about this?” he asked.

Being the know-it-all college students we were, a number of creative and robust solutions were floated. They ranged from creating billing systems for tape allocation, to allocating departmental tape quotas, eliminating tape in the office, and even installing surveillance cameras to thwart overuse. Our sage professor listened to our solutions until he couldn’t take it anymore. “People, it’s December!” he yelled. “The employees are using more tape because they are wrapping holiday presents! What do you do about this? BUY MORE TAPE!”

It was a moment I’ll never forget. Here all of us had been solving a problem that, when we stepped back from it, wasn’t much of a problem at all. How much could scotch tape really cost? It certainly wouldn’t be material to the company. Yet in business, people repeatedly obsess over problems that aren’t worth solving.

Is the Juice Worth the Squeeze?

Ask yourself “is the juice worth the squeeze?” Said differently, is the benefit of solving the problem worth the cost of designing, implementing and sustaining a solution? In general, the benefit of solving a problem should far outweigh the cost of solving it — including the inherent risks involved and the opportunity cost of your staff’s time and attention.

Eliminate the Required Referral

I remember reading a study on America’s specialist referral process — a procedure that required patients to acquire a referral from their primary care physician before seeing a specialist. The study found that the referral process was not only inefficient for both physicians and specialists, but it was costing patients more than visiting the specialist directly and being denied. The juice just wasn’t worth the squeeze. So they eliminated the referral requirement, saved a ton of money, and spun it as a customer-friendly enhancement — a true win-win for everyone involved.

Pay for Performance

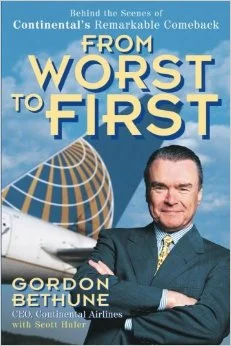

One of my favorite business books is From Worst to First — Gordon Bethune’s engaging story of Continental Airlines’ turnaround in the mid 90’s. The airline had one of the worst operational performance records of any carrier; and were particularly lousy with on-time arrivals. Bethune calculated that their unreliability was costing them $5 million per month, or more.

In response, he offered his frontline staff a monthly bonus of $65 each if they became one of the top three airlines in operational metrics. This offer would cost Continental $2.5 million each month, but Bethune saw the bigger picture. He knew this offer could solve the $5 million in wasteful spending, as well as improve their reputation and attract higher paying corporate clients. Over time, a more stable operation allowed Continental to better utilize gates, aircraft, staff, and other assets — making the juice (or return on the squeeze) much sweeter. If you’re interested in learning more about Bethune and his leadership at Continental, check out the book or this keynote speech.

Eliminating the Moderator

Image by Keith Williamson

When I was responsible for launching a global internal social network for 25,000 staff at my company, many members of my executive team wanted to require moderated approval of comments before they were posted to the site. So, I performed a quick squeeze/juice analysis:

The Squeeze:

· Hiring staff to review/approve comments, 24/6 (we were open 6 days per week, globally)

· Creating a negative user experience (that wasn’t dynamic or real-time)

· The idea of moderation could negatively impact staff morale

The Juice:

· Avoid the posting of something inappropriate or inaccurate

Conclusion: the case for moderation was not there. In addition, the platform already promoted personal accountability by displaying the person’s name and photo next to their comments. Thus, there was only an anticipated or perceived problem to solve, not even a real one!

By doing a quick analysis, I saved myself a bunch of work, expenditure, and my colleagues’ a user experience.

Next Time

When creating solutions to a problem, avoid the temptation to dive right into the answers that excite you. Instead, objectively and clinically examine what the value of solving the problem is in the first place. If the value is low, don’t waste your time developing solutions — and if it is high, balance the cost of implementing a solution with the value of the problem being solved.

Anchor image by AndruiXphoto